the ancient theater at Pergamon (photo by the Author)

Modern Stoics are interested in picking up the ancient tradition while at the same time updating it and molding it to modern times. For some reason, this is often considered a controversial thing, with flying accusations of cherry picking and dire warnings about the result not “really” being Stoic enough. But this is rather baffling, as philosophies, like (and more readily than) religions, do evolve over time, and indeed some of them have this attitude of constant revision built in. Just consider one of my favorite quotes from Seneca:

“Will I not walk in the footsteps of my predecessors? I will indeed use the ancient road — but if I find another route that is more direct and has fewer ups and downs, I will stake out that one. Those who advanced these doctrines before us are not our masters but our guides. The truth lies open to all; it has not yet been taken over. Much is left also for those yet to come.” (Letters to Lucilius, XXXIII.11)

(For one concerted effort at updating Stoicism see here; for some of the predictable growing pains of the movement see here; and check here for a smorgasbord of our modern critics.)

In fact, ancient Stoicism itself underwent a number of changes that are well recorded in both primary and secondary texts. The early Stoics used a different approach and emphasis from the late ones, and there were unorthodox Stoics like Aristo of Chios (who was closer to Cynicism and rejected the importance of physics and logic in favor of ethics), Herillus of Carthage (who thought that knowledge was the goal of life), and Panaetius (who introduced some eclecticism in the doctrine). There were heretics who left the school, like Dionysius of Heraclea, who suffered from a painful eye infection and went Cyrenaic.

Even within the mainstream, though, one gets fairly different, if obviously continuous, pictures of Stoicism moving from the early Stoa of Zeno and Chrysippus to the late Stoa of Seneca and Epictetus, with major differences even between the latter two. While an accessible scholarly treatment of this can be found in the excellent Cambridge Companion to the Stoics (especially chapters 1 and 2), I want to focus here on some obvious distinctions among the early Stoa, Seneca, and Epictetus, distinctions that I think both illustrate how Stoicism has always been an evolving philosophy, and provide inspiration to modern Stoics who may wish to practice different “flavors” of the philosophy, depending on their personal inclinations and circumstances.

I. The early Stoa: live according to nature and the four virtues

The major sources we have about the philosophy of the early Stoa, from the founding of the school by Zeno of Citium circa 300 BCE to when Panaetius (who is considered to belong to the middle Stoa) moved to Rome around 138 BCE, are Diogenes Laertius’ Lives and Opinions of the Eminent Philosophers, and a number of Stoic-influenced works by Cicero.

Reading through these sources, it is quite obvious that the early emphasis was on the teaching of the fields of inquiry of physics (i.e., natural science and metaphysics) and logic (including rhetoric and what we would call cognitive science) in the service of ethics:

“Philosophic doctrine, say the Stoics, falls into three parts: one physical, another ethical, and the third logical. … They liken Philosophy to a fertile field: Logic being the encircling fence, Ethics the crop, Physics the soil or the trees. … No single part, some Stoics declare, is independent of any other part, but all blend together.” (DL VII.39-40)

This changed in the late Stoa, as we shall see, when physics and logic were largely (though not completely) set aside, in favor of the ethics. But for the early Stoics, a reasonable understanding (logic) of how the world works (physics) lead to the famous Stoic motto: live according to nature.

“Nature, they say, made no difference originally between plants and animals, for she regulates the life of plants too, in their case without impulse and sensation, just as also certain processes go on of a vegetative kind in us. But when in the case of animals impulse has been superadded, whereby they are enabled to go in quest of their proper aliment, for them, say the Stoics, Nature’s rule is to follow the direction of impulse. But when reason by way of a more perfect leadership has been bestowed on the beings we call rational, for them life according to reason rightly becomes the natural life. For reason supervenes to shape impulse scientifically. This is why Zeno was the first (in his treatise On the Nature of Man) to designate as the end ‘life in agreement with nature’ (or living agreeably to nature), which is the same as a virtuous life … for our individual natures are parts of the nature of the whole universe.” (DL VII.86-87)

What about the virtues? Both the early and late Stoics subscribed to the Socratic doctrine of the unity of virtue, but the early ones were more keen then the late ones to talk about separate virtues (as we’ll see below, Seneca usually refers to “virtue” in the singular, and Epictetus hardly even mentions the word):

“Amongst the virtues some are primary, some are subordinate to these. The following are the primary: [practical] wisdom, courage, justice, temperance.” (DL VII.92)

And:

“Virtue is a habit of the mind, consistent with nature, and moderation, and reason. … It has then four divisions — prudence [i.e., practical wisdom], justice, fortitude [i.e., courage], and temperance.” (Cicero, On Invention II.53)

And how did they define the virtues?

“Prudence [practical wisdom] is the knowledge of things which are good, or bad, or neither good nor bad. … Justice is a habit of the mind which attributes its proper dignity to everything, preserving a due regard to the general welfare. … Fortitude [courage] is a deliberate encountering of danger and enduring of labour. … Temperance is the form and well-regulated dominion of reason over lust and other improper affections of the mind.” (On Invention II.54)

It should be noted that courage has an inherently moral component to it, it doesn’t refer just to rushing into a situation regardless of danger:

“The Stoics, therefore, correctly define courage as ‘that virtue which champions the cause of right.’” (Cicero, On Duties I.62)

II. Seneca: virtue and role models

When we move to Seneca, the emphasis shifts rather dramatically. Even though Seneca wrote a book on natural science, the overwhelming majority of his writings are on ethics. He rarely mentions individual virtues, talking instead of virtue in the singular. Consider:

“There is the whole inseparable company of virtues; every honourable act is the work of one single virtue, but it is in accordance with the judgment of the whole council.” (Letters LXVII. On Ill.10)

And:

“The matter can be imparted quickly and in very few words: ‘Virtue is the only good; at any rate there is no good without virtue; and virtue itself is situated in our nobler part, that is, the rational part.’ And what will this virtue be? A true and never-swerving judgment.” (Letters LXXI.32)

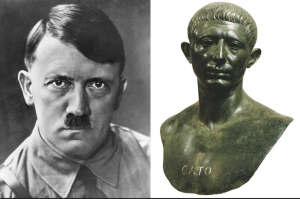

Moreover, Seneca puts a lot more emphasis than earlier Stoics on the importance of role models:

“Choose therefore a Cato; or, if Cato seems too severe a model, choose some Laelius, a gentler spirit. Choose a master whose life, conversation, and soul-expressing face have satisfied you; picture him always to yourself as your protector or your pattern. For we must indeed have someone according to whom we may regulate our characters; you can never straighten that which is crooked unless you use a ruler.” (Letters XI.10)

That is why I devoted an entire section of this blog to the exploration of role models, both ancient and modern. They are a great practical tool not just because they provide us with examples of ethical behavior to use as inspiration and to do our best to imitate, but also because our very choices of role models tell us a lot about our values and help us reflect on them.

As Liz Gloyn has commented in her The Ethics of the Family in Seneca, one can read the 124 letters to Lucilius as a bona fide Stoic curriculum, and it does not look at all like something Zeno or Chrysippus would have used. One gets a distinctive impression that Seneca has decidedly moved away from theory and into pragmatics, which foreshadows, of course, the great late innovator of Stoicism, Epictetus.

III. Role ethics and the three disciplines

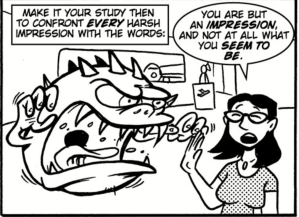

Among modern Stoics Epictetus is most famous for his clear statement of the dichotomy of control (see Enchiridion I.1), which with him becomes a dominant component of Stoic philosophy, and which underlies his famous three disciplines: desire, action, and assent.

“There are three departments in which a man who is to be good and noble must be trained. The first concerns the will to get and will to avoid; he must be trained not to fail to get what he wills to get nor fall into what he wills to avoid. The second is concerned with impulse to act and not to act, and, in a word, the sphere of what is fitting: that we should act in order, with due consideration, and with proper care. The object of the third is that we may not be deceived, and may not judge at random, and generally it is concerned with assent.” (Discourses III.2)

The dichotomy of control, the all-important distinction between what is in our power (our values and judgments) and what is not in our power (everything else) is an application of the virtue of practical wisdom, to which Cicero above referred to as the knowledge of things that are truly good or bad for us. It is most directly connected to the discipline of desire, which trains us to desire what is proper (i.e., what is under our control) and not what is improper (what is not under our control), but it really underlies all three Epictetian disciplines.

Epictetus, like Seneca before him, emphasizes practical philosophy, telling his students over and over that if they were there just to learn Chrysippus’ logic they were wasting their time (and his):

“If from the moment they get up in the morning they adhere to their ideals, eating and bathing like a person of integrity, putting their principles into practice in every situation they face – the way a runner does when he applies the principles of running, or a singer those of musicianship – that is where you will see true progress embodied, and find someone who has not wasted their time making the journey here from home.” (Discourses I.4.20)

Which is presumably why he developed an elaborate type of role ethics, as brilliantly discussed by Brian Johnson in his The Role Ethics of Epictetus: Stoicism in Ordinary Life. Brian points to this passage in the Discourses were Epictetus lays out the primary role of being human, contrasted with the secondary roles we all take on, some because we choose them, some because they are assigned to us by circumstances:

“For, if we do not refer each of our actions to some standard, we shall be acting at random. … There is, besides, a common and a specific standard. First of all, in order that I [act] as a human being. What is included in this? Not [to act] as a sheep, gently but at random; nor destructively, like a wild beast. The specific [standard] applies to each person’s pursuit and volition. The cithara-player is to act as a cithara-player, the carpenter as a carpenter, the philosopher as a philosopher, the rhetor as a rhetor.” (Discourses III.23.3–5)

This, according to Johnson, is a sophisticated elaboration of and advancement upon Panaetius’ four personae, a theory used by Cicero in the first volume of De Officiis: our universal nature as rational agents; what we can be by way of our natural dispositions; what we are as a result of external circumstances; and the lifestyle and vocation we choose.

This is why Brian disagrees with the famous — and widely accepted in modern Stoic circles — notion proposed by Pierre Hadot of a tight relationship among the three disciplines of Epictetus, the classical four virtues, and the three fields of inquiry (physics, logic, and ethics). I summarized Hadot’s approach here (see especially the diagram accompanying the post), but the more I think about it the more it seems both too neat and too strained. Too neat because it seeks to make coherent sense of different ideas that were deployed by the Stoics in a different manner when teaching five centuries apart from each other; and too strained because there just isn’t any good way to make things fit given that there is precious little evidence that Epictetus was thinking about the four virtues (or even the three fields of inquiry) when he articulated his three disciplines.

The upshot: a curriculum for modern Stoicism

If my analysis is even approximately correct, then this is a reasonable way to summarize the evolution of ancient Stoicism:

I want to stress that the implication is most definitely not that later iterations are better than early ones. “Evolution” here simply means what the root of the word indicates: change over time. In fact, I think these three approaches are different ways of interpreting the same basic Stoic philosophy, by putting the emphasis in different places as a function of the style of the teacher and the audience of students one is addressing. Ancient Athens was culturally distinct from imperial Rome, and Seneca definitely had a distinct temperament compared to Epictetus.

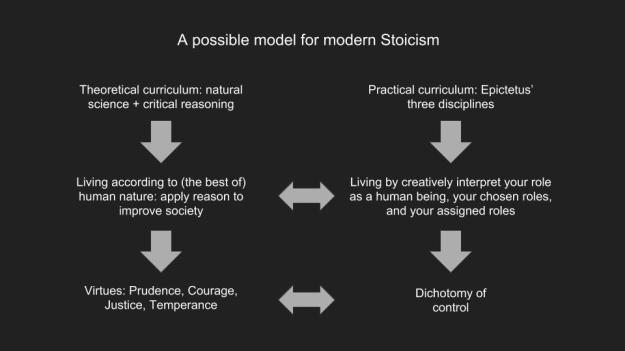

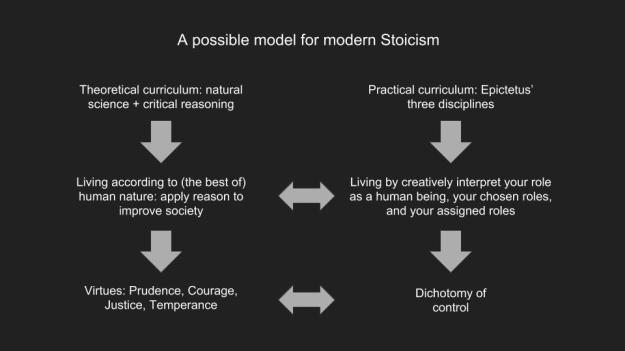

What does it all mean for modern students of Stoicism? The next slides is my own attempt at reorganizing the same material in a way that makes sense for contemporary audiences and could serve as the basis for a curriculum in modern Stoicism.

To begin with, notice the distinction between a theoretical and a practical approach (first row). Both should be deployed, as Stoicism is not just a bag of tricks, it is a coherent philosophy of life. A modern Stoic would be well served from learning the basics of natural science, developing a grasp of our best ideas about how the world actually works, so to avoid as much as possible buying into questionable views of reality. She should also acquire basic training in critical reasoning, so to be able to distinguish sense from nonsense and arrive at the best possible judgments in her life. The idea is the same one informing the ancient notion that in order to live a good life one has to appreciate how the cosmos is put together and has to be able to reason correctly about it.

The practical counterpart of the curriculum could be based on the Epictetian disciplines, which still provide a useful framework to actually practice Stoic philosophy, especially when tackled in the sequence envisioned by Epictetus. We still need to get better at redirecting our desires away from things that is improper (Stoically speaking) to want and toward things that is proper to want. The next step is to put our newly acquired practical knowledge into action, by behaving properly in the world, which largely means treating others justly and fairly. Finally, for the advanced students (as Epictetus suggested), we can refine our practice by paying careful attention to what exactly we should or should not give assent.

The second row in the diagram draws a parallel between two ways of thinking about how to live a eudaimonic life. On the left we have the theoretical understanding: we want to live following the best part of human nature, which for the Stoics very clearly meant to apply reason (our most distinctive faculty in the animal world) to improve society (because we are highly social beings who only thrive in a group). On the right we see Epictetus’ very practical way to put this into action: his role ethics. Notice two things, however: first, the most fundamental of our roles is that of a human being, which implies a cosmopolitan (as opposed to a nationalistic) stance. Second, that our specific roles in society can be interpreted creatively, which means, for instance, that just because one is, say, a mother, it does not follow that one should behave as a patriarchal society would want her to behave. If patriarchy is unjust (and it is), then a Stoic woman is under ethical obligation to play her role as mother to her children creatively, and if necessary in opposition to accepted social norms. (Needless to say, this applies to fathers and their role, and to pretty much any other role we play in life, whether given or chosen.)

The final row in the slide recovers a theoretical role for the classical cardinal virtues of prudence, courage, justice, and temperance, because I find them useful in order to provide a general framework for thinking about how we ought to behave. The practical counterpart is Epictetus’ dichotomy of control: every time we remind ourselves that some things are up to us and others are not, we then have to decide how to act on the first set and how to best ignore the second set. And our moral compass is provided by, you guessed it, the four virtues.

As you can see, Stoicism has always been a dynamic philosophy, responding to challenges from rival schools (Academic Skeptics, Epicureans, Peripatetics), to changing cultural milieu (Athens, Rome), and as a function of who was practicing and teaching it (Zeno, Seneca, Epictetus). There is no reason why this should not continue into the 21st century and beyond, now that we are responding to new challenges (Christianity, Existentialism, even Nihilism), that the culture has changed again (and has become more global), and that new teachers have emerged (Larry Becker, Don Robertson, Bill Irvine, hopefully yours truly, and many, many others). However you do it:

“Do what is necessary, and whatever the reason of a social animal naturally requires, and as it requires.” (Meditations IV.24)

Welcome to How to Be a Stoic! It began back in March ’15 as a blog to track my personal journey into modern practical Stoicism. The blog has now moved to Patreon and I hope you will follow me there.

Welcome to How to Be a Stoic! It began back in March ’15 as a blog to track my personal journey into modern practical Stoicism. The blog has now moved to Patreon and I hope you will follow me there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.